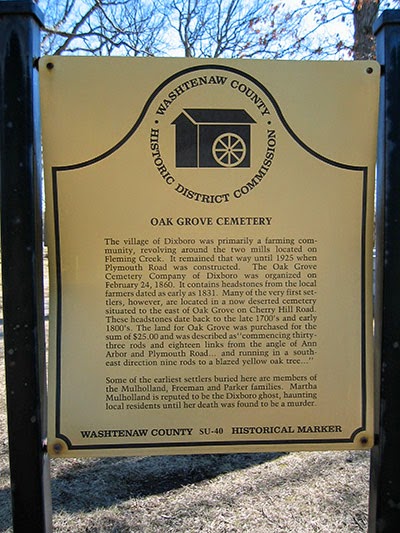

Of course, the kind of records used in genealogy have very little to say about the realities of ghosts, and after so many years, about the possibilities of poison or dead bodies deposited (or not) in local wells. But even without the dramatic touch of the Dixboro Ghost (see Part 1), the story of John Mulholland and James Mulholland is an interesting one.

Their story begins some years before Martha Crawford, the supposed Dixboro ghost, appears on the scene from Canada. In its broad sweep, it is about a large Irish family that immigrated to the United States from County Monaghan. While there are a lot of Mulhollands and an equal number of tales, for this one the focus is on James Mulholland, the first to arrive in Washtenaw County, Michigan Territory about 1826; in 1829 he first appears in county court records. His slightly older brother John came in 1831, having traveled from Ireland through Canada to Michigan. Their immigration dates and homeland are documented in 1834 court records of their "declaration of intent" to become naturalized citizens. Younger brother Sam arrived with John but is not part of the ghost legend.

Buying Original Land Patents in the Michigan Territory

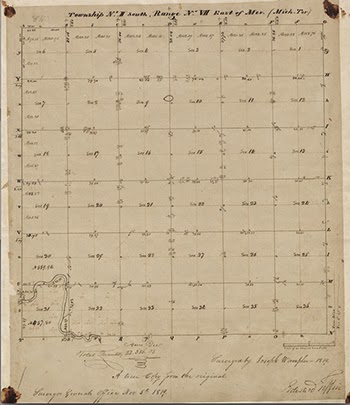

The Michigan territory as it was known back then was intended to be used for homesteads as a reward to those who fought in the war of 1812, but with rumors spread that it was a land of swamps and disease—possibly by early settlers who didn't want to see a land rush around their scenic new farms—few veterans took up the offer. In 1820, legislation opened the land for purchase by anyone with the cash to buy, and slowly over the next decades the land was sold off, with the more southern parts going first.

|

| Original U.S. survey of Superior Township, Michigan, 1819 |

Purchasing homestead land was not an easy process, and even back then the bureaucracy could make buying a long and complicated task. The government had done official surveys of Michigan, laying out counties in neat squares and subdividing these into parcels within townships described by geographical references rather than names which made up the areas available for sale. Even today the remnants of the early land division and sales can be seen in the square fields and straight tree lines bordering rural farms still defined by the early survey.

Once a person had sufficient cash to purchase a parcel, he had to get a survey done based on the government township borders, be sure the parcel was not already sold, take the survey and cash to the land office that had the authority to make the sale, register a cash receipt, then wait for the land patent to arrive from far-away Washington DC. The patent next had to be registered with the local officials so the land could be put into the usual circulation of sale and inheritance through deeds. In the case of Washtenaw County, the land office was in Detroit, a good distance for these early settlers when they had to travel on horseback and without many roads or inns along the way, and cash was something that few farmers had to spare.

According to the 1881 History of Washtenaw County, the Mulhollands were a family of weavers in Ireland, but their professions shifted to farming and other trades after arriving in the U.S. James and John Mulholland worked diligently to earn money to buy the kind of large farms not attainable in their homeland. By 1832, the brothers obtained their first land patent for 80 acres in Section 18 of Superior County, the same section in which Captain James Dix, the founder of Dixboro, bought in that year. In 1835, after more of the family had arrived from Ireland, James purchased another 40 acres in Section 20, a parcel which was sold to his father Sam sr. and where my great-great grandfather Samuel Mulholland jr later farmed. The description of this latter property looked like this, rather arcane for those who are not surveyors or deed writers:

Sw 1/4 of the Nw 1/4 of Section 20 in township 2 South of Range 7 East [Superior] in the District of lands subject to sale at Detroit Michigan Territory containing 40 acres (Land patent, certificate 8030, issued 9 Oct 1835, to James Mulhollan of Washtenaw County Michigan Territory)

John and James had continued to buy homestead property in Michigan, expanding beyond Washtenaw and picking up large parcels in Livingston and Ingham counties in 1837. In a history of Livingston county, it was pointed out that the Mulhollands never lived on their homestead but sold it off for a profit in the following two years.

The patents show John and James held all but the Section 20 lands in common not in joint tenancy. Just prior to his death and in failing health, court records show John arranged for a division of the land held by himself and his brother. While John attempted to get his estate in order before his death, he was unable to get all in place.

With John's death in June 1840, Martha became the administrator of John's estate under Probate Court order to produce an appraisal of "goods, chattels, rights, and credits" in 1840. When the estate had not been appraised, James went back to the Probate Court in 1841 indicating that it needed to be done and that there were debts to be settled and he was the primary creditor. The court ordered a $1000 bond to bring in appraisers, but in 1842 Martha herself indicated she was not able to comply due to failing health, and requested that the court appoint a new administrator to review the estate. Despite continued claims and counterclaims, the estate remained unsettled until 1846, when John's father Sam sr. petitioned the courts to appoint his sons Sam jr and William, John's younger brothers, as administrators. In the petition dated 19 Jan 1846, Sam was sworn as stating:

The undersigned Samuel Mulholland would represent that he is the Father of John Mulholland late of Superior in said county deceased that said John Mulholland died at Superior aforesaid sometime in June in the year AD 1840 intestate leaving real and personal property to be administered. The undersigned further represent that the said deceased has no children now living and that it is necessary that some person or persons should be appointed to settle the estate of said deceased as there are debts to be collected and paid. The undersigned would waive his right to administer said estate on account of his extreme old age and requests you to appoint Samuel Mulholland jr and William Mulholland brothers of said deceased and sons of your petitioner administrators for said estate upon their [young hand?] for the faithful discharge of that trust.

With Martha's death in 1845, eventually most of John's remaining estate formally went to his stepson Joseph Crawford, Martha's son from her first marriage as there was no will. If James felt some resentment for Martha's teenage son, not even a member of the Mulholland family, inheriting the land and money he had worked so hard to attain with brother John, and likely had further plans to exploit, it would not be a surprise.

Growing Township, Growing Families

Interestingly, the ghost story has little to say about family life, perhaps because this makes the players more human and less ominous. While relationships among James and Martha were perhaps strained, the participants in the ghost story had much broader lives.

|

|

A view of Dixboro, Michigan from the Commons in 2004

|

James left Ireland and immigrated to Quebec, Canada in 1826 and before 1829 was living in Washtenaw, Michigan. He was an early settler in Dixboro founded by John Dix. In county civil court records from November 1829, James appeared in the court with Dix for an indictment of $50 owed to the United States. The indictment does not indicate the reason for the assessment but it must have been paid, as the two were released on their own recognizance and ordered to pay up or appear at the next court session. They do not appear again at the next court session.

The exact date that James married his first wife, Ann Mulholland, is unknown as is her maiden name, although some reports indicate she came with him to Michigan. By the time of the 1830 census of Panama Township, later divided into Superior and Salem Townships as we know them today, James is listed as living with a woman (most likely his wife Ann) between the ages of 20 and 30, about the same age as her husband, and with a son under five. In 1834, the household had grown to five with the addition of another adult male, presumably brother John who immigrated in 1831, and a daughter under 5. These early census records did not have names for any but the head of household. As a result, the names of most of James' children have been lost to us unless new records are discovered. Only one son of James is known from a sad story of a toddler who got too close to the fireplace and burned to death when his clothes caught fire. James jr. died after his mother Ann, living from 1835 to 1838.

Martha Crawford and son were not listed as living with her sister Ann's family in mid-1834 when the census data was recorded. She is reported to have arrived in mid-1835 from the later court hearings related to her enigmatic death. John and Martha were married in December 1835 when John was 33. When John died in 1840, he left behind a son reportedly born in 1836 but who died later in the same year as his father.

James remarried to Emily Loomis in 1838 after Ann's death about 1836-7, all before John then Martha died. While the ghost story claimed James and his second wife had only one stillborn child, in fact they had at least two more children. Further, he and his family did not flee immediately after the 1846 inquest, nor were any criminal charges ever filed against him. In an interesting vignette reported in a Universalist Church publication in 1847, Emily Loomis Mulholland's death is noted, indicating the family remained in Superior Township:

Death. In Superior, on Ap 25 last [1847], Mrs. Emily, wife of Mr. James Mulholland, in the 34th year of her age. She has left a husband and four small children, the youngest about four weeks old, also an aged Father and Mother, to mourn the loss of a faithful child and virtuous Mother. She has been a member of the Universalist Church in Ann Arbor about nine years. (published Dec 1847, The Expounder of Primitive Christianity, v. 4, p. 175)

By 1850, only Martha's son, Joseph Crawford, remained in Superior Township of all the characters from the Dixboro Ghost Story. He retained his inheritances, with the records showing he owned property worth $1000. Joseph married in 1855, and by 1870 he too had left Superior Township, moving initially north in Michigan to Livingston County where other Mulhollands had settled, and later to Ogemaw where he became one of those revered early settlers, dying shortly after his move there.

Mounting Problems for James Mulholland

For James Muholland, the evidence suggests his departure from Superior Township after the ghost inquest may have been as much about finding a wife or caretaker for his four orphaned young children rather than any guilt over what happened to his sister-in-law. He did not flee immediately as has been recorded in legend but did eventually move on, and over time, community sentiment eased after the initial hysteria brought on by the wild tales of Martha's ghost and perhaps gossip by a few who didn't like James. Whether the community feud also rendered family ties to his father and siblings is unknown, but Sam jr. did testify to the Probate Court in 1846 that there were unpaid liens on John's estate, perhaps providing some evidence the family was sympathetic to James's complaints.

Debts may also have contributed to the disappearance of James as suggested in earlier histories. His lands were seized by the courts for unpaid debts. Initially land in Section 19 of Superior was sold at public auction in late 1849 for debts owed by James, his brother-in-law William Loomis, and David Bottsford, another original land owner in Washtenaw County.

James debt problems continued to mount. Frederick Townsend petitioned for redress in the Detroit courts in February 1850 and as a result James' two remaining lots in Dixboro were seized by the sheriff of Washtenaw County. With no creditors coming forward after 15 months, the lots were auctioned at a sheriff sale in fall 1852. Townsend was allowed, rather conveniently, to purchase the two village lots owned by James for $100, far below the actual value. As history has since recorded, based on Michigan laws at the time, this process of land seizure and repurchase was a corrupt one in which a debtor could collect and profit with little evidence and often few others being aware of the court orders and sale.

The ending of the recorded ghost story stating it is uncertain where James Mulholland went remains true, as neither he nor his children have been located in official records after Emily's death in 1847 and with the loss of his property in 1850.