|

| One of the many stories in the Ann Arbor News, October 2000 |

The Dixboro ghost story has seen many retellings, beginning with newspaper accounts during an inquest in 1846 in the Ypsilanti Sentinel and the Ann Arbor True Democrat, a section in the 1400-page tome 1881 History of Washtenaw County, a 1962 review by a local historian, Russell E. Bidlack of court and newspaper records from the period, a chapter in Carol Freeman's 1997 book, Of Dixboro: Lest We Forget, and in many contemporary scary tales, often told near Halloween, in the Ann Arbor News and other local publications. Because of the official proceedings around the event, the outline of this tale is preserved in township and court records, and can be further supported by other official documents.

A Halloween Haunting by the Dixboro Ghost

According to the story, a carpenter working in Dixboro in 1845 rented a house where he claims to have seen a female ghost over several nights around Halloween. The spirit was reportedly a woman, Martha, who died in the house in June of that year under suspicious circumstances.

The background to the ghost tale begins when a widow Martha Crawford and her young son Joseph Crawford arrived in Dixboro, Michigan from Canada in 1835 after the death of her husband. Martha moved in with her sister, Ann Mulholland, who was married to James. It wasn't long after arriving in Dixboro that Martha remarried, this time to James' older brother, John Mulholland, in September 1835.

In some versions of the story, Ann told Martha a horrible secret about the Mulholland brothers just before her sister's wedding. Martha tried to flee back to Canada before her nuptials, but was threatened by James should she attempt to leave and the wedding went forward for John and poor Martha.

About a year after the wedding, James' wife, Ann Mulholland, not yet 30, died in 1837, suffering before her death from some strange mental condition. Martha's young husband John died next in 1840. In the years following her husband's death, Martha began to exhibit the same strange mental instability as her sister. Despite treatment by a local medical practitioner, Martha continued to worsen, dying in summer 1845.

After Martha's death, a traveling carpenter, Issac Van Woert, and his family, moved into the now empty house in September 1845 only months after Martha had died. The house had been inherited by Joseph Crawford, Martha's now teenage son from her first marriage. The carpenter had only been in the house a short time when a feminine spirit appeared to him reportedly saying "They kilt me." She was a middle-sized woman holding a candle in her left hand and wearing a white, loose gown with a scarf bound round her head.

Upon inquiring from neighbors, the carpenter learned of Martha's peculiar death in the house earlier that year. As the nights progressed, the ghost continued to appear to the carpenter nine times over a several week period in October and November. The ephemeral female claimed she was murdered by her brother-in-law James. She expressed her fears that now her son Joseph was in danger and would be harmed by the same people.

"He has got it," the ghost is reported to have said. "He robbed me little by little until they kilt me. They kilt me; now he has got it all."

She also suggested her murderer had killed a wandering peddler and thrown the body down a local well.

Although no one suspected foul play when Martha died, with the report of the ghost's message, her brother-in-law James Mulholland fell under suspicion. Before her death, the scheming James was reported to be after the money and property Martha had inherited from the estate of her husband John. James had tried to become Martha's guardian when she began to act strangely so he could manage her affairs. In the years after John's death, Martha became increasingly melancholy and downcast, suffering from nightmares and horrid dreams, according to an anonymous source reported in local newspapers several years after her death. Just before she died, Martha was said to have told an attending doctor from Ann Arbor a terrible secret about James that was never publicly revealed, possibly the same one told to her by her sister Ann.

|

| The Dixboro Store in 2004: A smaller house built by James Mulholland was the start of this building. John and Martha Mulholland lived in a house across the street. |

The 1846 Inquest

After the carpenter reported his story to the authorities, a judge ordered Martha's body exhumed. The well was also searched although no body was found. The local coroner who examined Martha's corpse pronounced she had died of poison from an unknown source. Despite formal hearings in January 1846, no evidence was produced to show how Martha had been murdered or by whom.

|

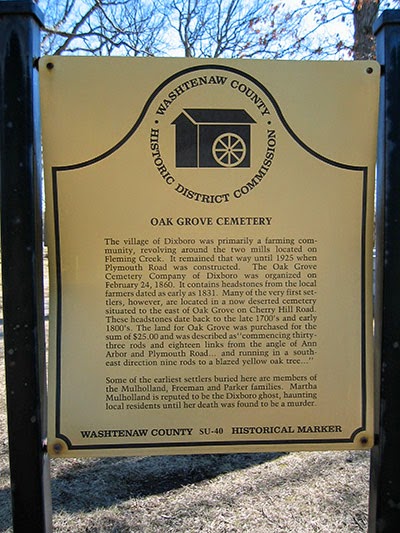

| Dixboro Cemetery entrance sign: Early Mulhollands and a ghost |

According to an anonymous author labeled "SPECTATOR" who wrote a newspaper article widely circulated several years later, Martha had been "often subjected to the ill usage of her brother-in-law," who seemed to take every opportunity to make her life "as full of trouble as possible.” It was the opinion of many of the neighbors that James Mulholland's "only study was how he might possess himself of the property which had been possessed by his brother and was now in the possession of his unfortunate widow."

As the ghost story spread, James found life less than pleasant in the small, tight-knit community, and rumors spread of criminal proceedings in March 1846. James was reported to have left immediately after the inquest, along with the patent-medicine practitioner who had treated Martha and by association was assumed to have been an accomplice in the poisoning before her death. James' land was sold at a sheriff's sale in 1852 and he was not heard of again.

Even in the 1881 History of Washtenaw County, there was a recognition that James was perhaps unfairly condemned by those in the community who wanted him gone.

The ghost excitement of 1845 was one of those strange uprisings of popular superstition which vary the monotony of life, and result in the accumulation of valuable experience….Many are inclined to believe the story of the “Dixboro Ghost,” but the great majority ascribe the cause of all this excitement and trouble to a well-laid conspiracy, having for its object the banishment of a medical man from the settlement, and the disgrace of others. If this were a fact, the conspiracy succeeded; the persons stigmatized by the spector of Mrs. Mulholland left the district within a brief space of time. (p. 1071-1073)

According to the Freeman book, the supposedly haunted house that had belonged to John and Martha Mulholland burned in the 1860s or 1870s. The foundations were still there years later behind 5164 Plymouth Rd.

More on the Dixboro Ghost Story: Read Part 2 to learn the facts!

Bibliography

Links to more versions of the Dixboro Ghost Story. The best researched is by historian Russell E. Bidlack published in 1963 by the Washtenaw Historical Society. Both the Dixboro Store and article by Koch-Krol have the full affidavit submitted by Isaac Van Woert.

- Russell E. Bidlack, 1963, "The Dixboro Ghost." In Washtenaw Impressions, a publication of the Washtenaw Historical Society, v 14, no 6, p. 10-16.

- 1881 History of Washtenaw County, Chas. C Chapman & Co (via Google Books), "The Dixboro Ghost"

- From the Dixboro General Store web site: The Famous Dixboro Ghost

- Cindy Koch-Krol, 2013, My Haunts Blog, The Ghost of Dixboro; and her fictional 2016 novel, The Ghost of Dixboro

- M-Live YouTube video from 2016, Did You Know The Story Of The Dixboro Ghost?

- A philosophical commentary on the ghost story by Mark A. McDonald

- From the Ann Arbor News

2008: "Dixboro Ghost Part of Local Lore"

1972: "Will Dixboro Ghost Make Her Rounds Tonight?"

No comments:

Post a Comment